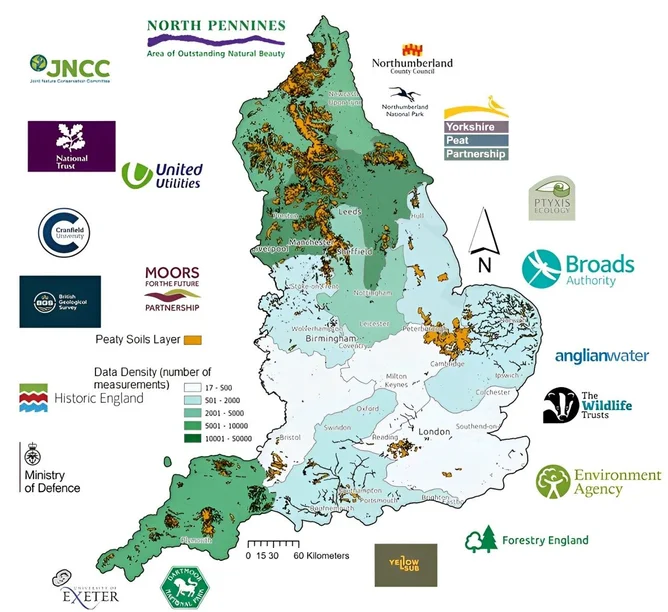

England’s natural peatlands, holding 3.2 million tonnes of carbon, are the focus of a new conservation project by Natural England, Microsoft and Defra.

The UK’s peatlands, covering 12% of the country, are more than just striking landscapes. They serve as vital carbon sinks, locking in an estimated 3.2 billion tonnes of carbon, whilst also providing ecosystem services such as flood management and biodiversity support.

Yet, only 22% of these peatlands remain in a near-natural state. Natural England’s innovative AI for Peat programme, developed in collaboration with Microsoft and Defra, is tackling this issue by restoring these degraded ecosystems using advanced artificial intelligence.

Mapping peatland damage

Restoration of peatlands begins with understanding their condition, a process that traditionally relied on slow and laborious manual surveys. According to Karen Rogers, Lead Advisor in Natural England’s Cheshire and Lancashire Area Team, this was a major bottleneck. “We can’t start to restore them until we know their current condition and where any damage is located,” she says.

Degraded peatlands, impacted by factors like overgrazing, drainage and pollution, risk emitting vast amounts of carbon into the atmosphere. The scale of this threat is immense—584 million tonnes of carbon could be released into the atmosphere from degraded English peatlands alone.

Time is of the essence, so, in the hunt for a more efficient and holistic mapping method, Natural England decided to turn to AI for help.

Harnessing AI to map peatlands

In 2021, a proposal for AI-driven mapping won initial funding through the Civil Service Data Challenge, paving the way for the AI for Peat project.

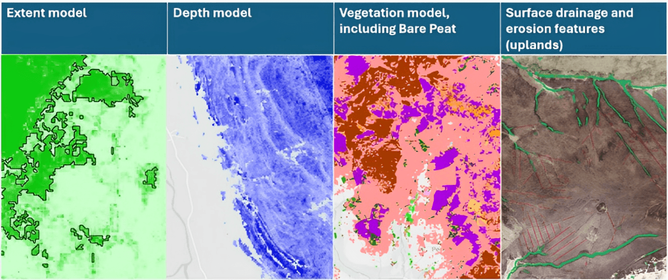

By employing deep learning models on Microsoft Azure and Azure Databricks, the project aims to identify peatland features such as grips (drainage channels) and gullies using high-resolution aerial imagery.

“This is life-saving work, so why wouldn’t we support it with leading technology?,” asks Joe Hillier, Head of the Analytics Directorate at Natural England. “We’re at the cusp of AI’s potential and projects like this exemplify that.”

The challenges, however, are significant. Processing aerial imagery at a scale of 12.5 centimetres per pixel requires vast computational power. Defra’s Data and Analytics Science Hub (DASH), launched in 2022, provided the essential cloud-based infrastructure.

Olivia Newport, Head of DASH, says: “We want to bring the analytics and science community together, supporting them with scalable compute and innovation.”

From national mapping to local restoration

The integration of AI into peatland mapping has transformed the restoration process. Instead of spending years manually mapping, local teams can now use AI-generated data to identify areas requiring intervention. “We can load the output mapping layers onto a tablet and follow the features in the field,” Karen explains.

“It makes everything so much easier. Instead of mapping features, we’re asking ‘What intervention should I be making here?’”

While the technology marks a significant leap, challenges remain. Variations in vegetation and imagery can hinder the accuracy of AI models. “We’re now thinking about how to ensure the models can be accurately applied across the whole of England,” says Martha Tabor, Data Scientist at Defra.

Despite these hurdles, the programme’s potential is immense. “If we can add carbon metrics to the mapping, we’ll get really useful digital datasets,” says Anne Williams, Project Manager of Natural England’s AI for Peat. She envisions the development of a digital twin to model the impacts of restoration interventions, providing critical insights for future projects.

Building a foundation for broader collaboration

The AI for Peat project is all about cross-agency collaboration. The teams from Natural England, Defra and industry partners like Microsoft and Databricks all play their part in this undertaking.

So far, the results have been promising. Peatland restoration efforts are now accelerating, but – perhaps more importantly – the groundwork has now been laid for the UK government’s adoption of AI across other its other environmental initiatives.

Paul Sinclair, Head of Data Exploitation at Defra, reflects on the collaborative spirit that has driven the project’s success. “Accepting that no one gets things right first time is really important. Being willing to take risks helps push the boundaries of what’s possible,” he explains.

For many involved, the significance of the work goes beyond technical innovation.

Olivia Newport sums up the motivation behind the programme: “We’re all here because we want to make a difference. It’s incredibly rewarding when technical skills and environmental goals come together to solve intractable problems.”